If you ask most green housing practitioners, they’ll tell you that the integrated design process is crucial if you want a successful outcome of truly sustainable communities. But what is the integrated design process, and how do you make it work in practice? In this episode of Green in Action, host Kimberly Vermeer speaks with five green leaders about how they apply the integrated design process in their work. Guests include: Tara Barauskas, Executive Director of the Community Corporation of Santa Monica; Ray Demers, Senior Director of Design Leadership Initiatives at Enterprise Green Communities; Krista Eggers, Vice President of National Initiatives at Enterprise Green Communities, Anne Torney, Partner at Mithun; and Walker Wells, Principal at Raimi + Associates and Kim’s co-author of Blueprint for Greening Affordable Housing, Revised Edition.

Topics Discussed:

- The Integrated Design Process

- Integrated Design vs. Standard Design – what’s the difference?

- Using sustainable design to transform communities

- Tackling complex green building problems

- Transdisciplinary, mission-oriented collaboration

- The importance of making early design decisions with many stakeholders

- The charrette

Resources:

Blueprint for Greening Affordable Housing, Revised Edition

Community Corporation of San Diego

Enterprise 2020 Green Communities Criteria

Minisode Deep Dive: Integrated Design in Enterprise Green Communities

Integrated Design Diagrams from Mithun

Getting into Integrated Design

[Theme Music]

KIMBERLY VERMEER: Hello! I’m Kim Vermeer, host of Green in Action,the podcast where we celebrate stories of green leadership in affordable housing.

A guiding principle of green design is building healthy, energy efficient buildings that result in more sustainable communities. When you apply these ambitious green goals to the affordable housing field, you end up facing more complex challenges.

TARA BARAUSKAS: I went on the roof of a building that was completed and found my solar panels in the shade. And that was a real drag [laughs]because I realized that had there been a little more thought into the solar panel layout early on, it would have resulted in a better configuration of solar panels and the roof as a whole you know, microcosm, I feel unto itself, and where a lot more attention needs to be paid.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: That’s Tara Baruaskas, now Executive Director of the Community Corporation of Santa Monica, talking about an experience from earlier in her career.

Bringing green building practices to affordable housing development is still relatively new territory. Creating housing that’s both sustainable and affordable is difficult. And sometimes, mistakes are made – even ones as fundamental as solar panels ending up in the shade. As Tara discovered, the standard design process didn’t deliver the desired green results. So how do practitioners deal with these challenging layers of complexity?

One solution lies in tackling this complexity with a new approach – what practitioners call the “integrated,” or “integrative,” design process. This process takes a holistic approach to envisioning the mission of a project – integrating all of the design disciplines with the aim of achieving a greener building for the people who’ll live there.

So, I asked some experienced green leaders to help us learn more about integrated design, from how it differs from the standard process, to how it can equip us to build better projects.

WALKER WELLS: You can think of a piece of fabric and there’s threads going one direction and going another way. And collectively they add up to something that makes a pattern and makes something holistic, unified, hopefully beautiful. And in a building, you have all of these different components that are going on and I think integrated design is,its intent is to look at all of those component parts and identify how they can cooperate with each other to produce a building that’s better for the environment, but probably equally, if not more importantly, better for the residents.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: That’s an evocative description of Integrated Design from Walker Wells, my co-author of our book, Blueprint for Greening Affordable Housing, and a strong advocate for the Integrated Design Process.

I started my exploration of integrated design by asking Walker why he felt it was important to include a chapter on integrated design in our book.

WALKER WELLS: Green building has a lot of components to it, a lot of sort of philosophy about what we’re trying to accomplish. But then one asks, so how do you do it? And I think my conclusion is that integrated design is the primary method for achieving green buildings.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: But from my conversation with Walker, I wondered: how did integrated design develop as a discipline for achieving green buildings?

[Music]

KIMBERLY VERMEER: To understand why integrated design is so fundamental to green building, we need to understand the ways that it’s different from standard design practice.

I asked Anne Torney, a partner at Mithun in California, and an experienced architect and urban designer, about this question.

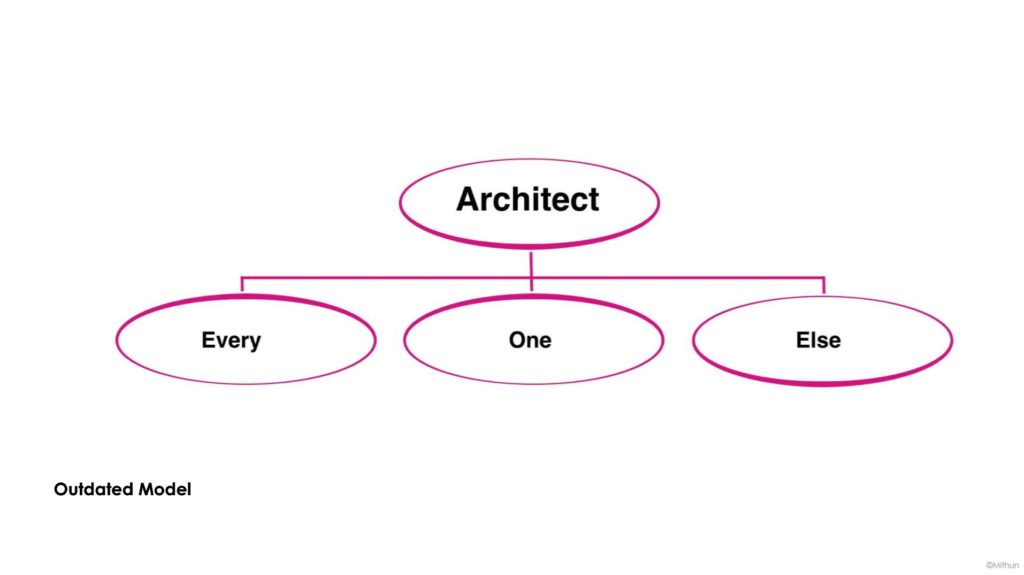

ANNE TORNEY: So the classic model, as you mentioned, for the architect, is that the architect is at the center and there’s kind of everyone else kind of rotating around them. You know, if you can imagine a kind of a wheel with the architect at the center and the mechanical engineer plugs in and somewhere the client plugs in and the landscape architect plugs in and your acoustical engineer and unfortunately, at least my generation, that’s how we were educated to think about design.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: Anne described the traditional process where the owner and architect would meet to determine the building program – the types of uses and the square footage to assign to each use – and then as design continues, other disciplines like structural and mechanical engineers are plugged in, on an as-needed basis.

But that approach can lead to communication and coordination problems during construction and after completion.

Tara, the developer, had another story to share:

TARA BARAUSKAS: I remember being three quarters of the way done with construction and a drastic change had to be made, meaning changing where doorways and windows were going to go, after we were almost all built out. And I remember that feeling of frustration that we’re almost done with construction and now we’re making major changes and the frustration that came from the entire team as a result of that. And obviously, the huge cost and time delays that resulted was something I never wanted to repeat again after that.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: When I spoke with Krista Eggers, now the Vice President of National Initiatives at Enterprise Green Communities, she could relate. She shared a story from early in her career when she worked as a HERS rater. HERS stands for Home Energy Rating System.

KRISTA EGGERS: Sometime in that first year we got called to go check out a house that just wasn’t performing well, like the energy bills were really high. Nobody can figure out what was going on.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: When Krista and her team investigated this mystery further, they realized that the band joist, a wooden framing element between the first and second floor of the home, was wide open to the porch roof structure. So that meant, when the residents of the house were trying to heat and cool the air inside, that air would travel up into to the floor system, out through the porch roof, and then right on out of the house to the great outdoors. The uncontrolled airflow resulted in a situation Krista encountered, where residents were paying really high energy bills.

Again, we hear from Krista:

KRISTA EGGERS: You know, the framers who built this house didn’t sign up to their job knowing that they’d be creating a nightmare for the HVAC contractor a couple years later. But that’s what ended up happening. And many of these guys, even though they had been working on the same homes for decades together, had never talked with one another. And so it was one of those situations where, you know, wouldn’t it be great to consider this work up front and ward off those unintended consequences?

KIMBERLY VERMEER: It might seem like a lot of work to shift to a whole new design process. But from hearing these horror stories about miscommunications in the standard approach, I was ready to learn about new models.

I also spoke with Ray Demers, Krista’s colleague and the senior Director of Design Leadership initiatives at Enterprise Green Communities, and he summarized it pretty well:

RAY DEMERS: If you think making affordable housing while going through an integrated design process is hard, you should try not going through an integrated design process. It will be much more complicated. It will be harrowing. You won’t solve all your problems with an integrated design process, but you’ll get the answers a lot more quickly.

[Music]

KIMBERLY VERMEER:So, how do you re-frame the design process to be more integrative?

Our experts shared three strategies. The first is to take a different approach to project goals-setting and early planning.

Anne, the architect, described that new approach.

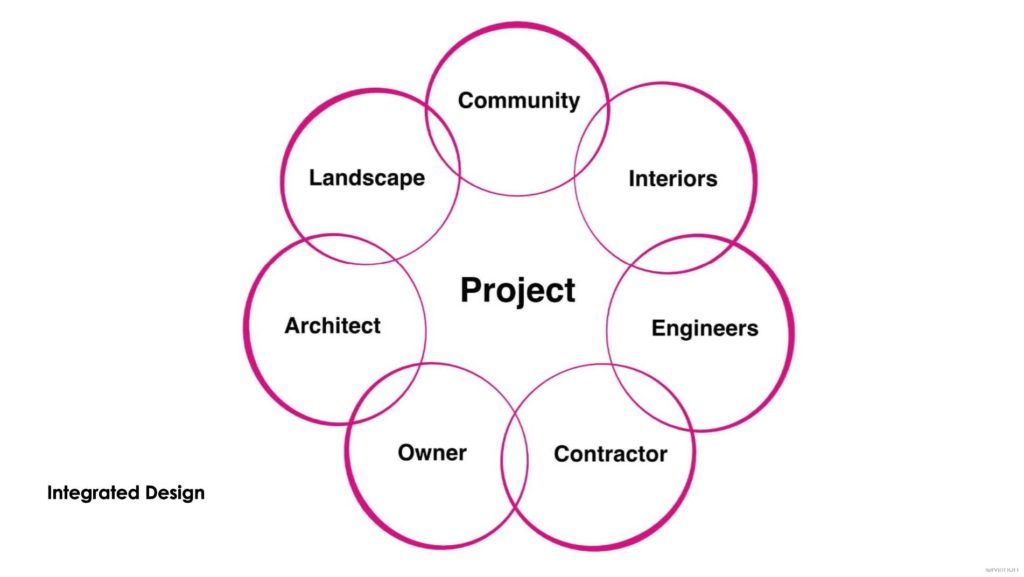

ANNE TORNEY: We have a diagram that we love to refer to which has the project at the center. And the spokes are really everyone involved with the project, you know, the architect, the mechanical engineer, the structural engineer, the client, the property management folks, the community partners. And so everyone has their kind of eyes on the prize, as it were, meaning like the best outcome for the project. However that is, however that morphs, rather than the center being the architect and the architects formal concept.

KIMBERLY VERMEER:And Tara describes this approach from the developer’s perspective:

TARA BARAUSKAS: We are sort of the conductor of the orchestra is the way I like to think of it. So we bring all the teams together and we choose them, you know, thinking about the successful outcome of our building, which is a building that’s efficient, that meets our budget and our timeline and is the wonderful place to live for our residents.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: As with conducting great music, Walker, the green consultant, describes how the collaborative process is crucial to creating something special.

WALKER WELLS If you’re in your car, or on the bus, or on your bike with your family and you realize that you’re four blocks away from this this particular project that we’re talking on, what would make you intentionally take your family by that building because you’re so proud of something about it?

KIMBERLY VERMEER: Developing that sense of mission as a group from the beginning makes ambitious green building goals more attainable.

The Enterprise Green Communities team feels so strongly about the power of integrative design that they’ve made it a core component of the Green Communities Criteria. In fact, in the latest 2020 Criteria they’ve strengthened the Integrative design sequence and added a Pre-Project Priorities survey that guides teams through a process to clarify project goals from the beginning.

KRISTA EGGERS: And I think what the crux of integrative design is, is recognizing that you’re so much better off spending time early on to really set that North Star goal in terms of listening to the community and identifying what relationship that people who’ll be living in the property want to have with where they’re going to be living. So that you can hold that as your North Star, that project mission as you go throughout the design process.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: Check out our mini-sode about the Enterprise Green Communities 2020 Criteria to learn more.

Ray, from Enterprise reminds us why it’s so important to start early.

RAY DEMERS: 90 percent of design decisions are made in the first 10 percent of the process. So having all of the partners involved with the project as early as possible is critical to making sure disciplines are coordinated, but more so that the project is going to meet the needs and ambitions of the communities that they serve.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: Of course, early planning presents both benefits and challenges! In our book’s chapter on Integrated Design, Walker and I discuss the relationship between early design thinking and the costs of going green. The earlier in the process, the more cost effective it is to get green in. And the later you wait, the more expensive it gets.

WALKER WELLS: At the early stages of a project, there are lots and lots of opportunities, and those are really the cost of a conversation or a one-hour meeting. We can say, “well, hey, maybe we should look at this or what about being a net-zero building or what about a grey water system?” That can be a 15-minute conversation, not very expensive. Later on, you have to spend time and money undoing things before you can even start doing new things. So there’s sort of a double cost to a lot of these undertakings.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: But that brings up a challenge for holding these early meetings: spending money upfront on a project can be hard for housing developers, who often secure funding for projects later on in the project timeline.

But that early funding is crucial to bringing the whole team together at the schematic design phase, which architect-speak for the early stages of a project when basic decisions are being made.

Anne described her experience with a recent project at Mithun.

ANNE TORNEY: I’m thinking of a project right now where we’re really frustrated and confounded because the early schematic design funding only allowed us to go partway through schematic design. And, we’re not able to bring the sub-consultants on board. And it’s frustrating.

KIMBERLY: In this situation, designers resort to using a workaround: calling people for informal input.

Creating this network of relationships where you can call in favors is one way to get early design input. But let’s be clear: it’s better if project managers can find a way to budget for some of this early work.

[Music]

KIMBERLY VERMEER: After rethinking the early planning process, the next step in integrative design tackles the design development phase. One tool I heard described a lot in this phase is a “charette.” So, what is a charrette?

In the Integrated Design context, a charette typically refers to an intense design and planning session which includes diverse stakeholders of a project. Often a charrette is a full-day meeting with as many project stakeholders participating as possible. It’s both a chance for developing project goals and for project teambuilding. As Anne puts it,

ANNE TORNEY: I always feel that one of the major benefits of a charrette is people are understanding who everybody else is on the team. It’s that relational aspect, not just the kind of problem-solving aspect. Everybody is kind of in it: curious, interested, connecting the dots, kind of like all as one brain, instead of a bunch of separate brains.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: Anne emphasized how charettes are useful for early relationship-building. Walker also stressed the importance of thinking of the charette as a part of a bigger ongoing design process.

WALKER WELLS: The charrette is a very important part of the integrated design process, but it is not the be-all and end-all of integrated design. And this is a common fallacy that can occur that people think, “oh, we’re going to have a charrette, or, we did a charrette and we did green building, we did integrated design, done.” And that’s not the case.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: Anne reinforced that message.

In her practice as an architect, Anne has reconceptualized the charrette’s purpose: from viewing it as a one-off tool, to considering it an initial catalyst in a larger process of building relationships and solving problems as a team.

ANNE TORNEY: We’ve found it’s great to have an initial kind of kick off. And there’s always too much to talk about in a day long discussion with a project. So, we’ve started sometimes doing what we call rolling charrettes where we’re not trying to do everything all in one meeting, which can be superficial. So in some ways, like a charrette is more, again, more of a mindset than an event. And I think that’s the most powerful thing for successful integrated design.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: In this way, the integrated design process requires check-ins throughout the design process, not just at the beginning.

Ray, too, views the integrated design process as iterative, rather than a one-time event.

RAY DEMERS: I would describe integrative design as a collaborative, problem solving approach. It’s not a period. It’s not a duration. It’s an approach to problem solving, and it is a problem-solving approach that tries to wrestle both with how decisions are made, but also why decisions are made, and it grapples with them in real time.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: Who gets to make those decisions?

[Short music]

KIMBERLY VERMEER: Well, we’ve learned about how important committing to early planning is, and how charettes can reshape the design development process. The third topic raised by our experts was strategies for expanding the voices included in project decision-making.

Here’s Walker:

WALKER WELLS: I used to have some aphorism that if we were going to have a meeting, we probably had a big enough room. But if we’re going to have a charrette, we gotta get a bigger room.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: You need that big room, not just for designers, but for the people who are going to live in and work in that place. Those people are the ultimate customers, regardless of who is paying for building it.

As Krista reminds us:

KRISTA EGGERS: We need the folks who will be living in the property, engaging in integrative design. We need the folks who will be responsible for keeping up the building and like ordering replacement filters involved in the design. We need the folks whose phone will ring if the building isn’t warm enough in the winter involved in the design.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: These conversations with the residents and property managers can completely reframe a development team’s understanding of the specific needs of a group.

Anne was working on a project that is under construction now, veterans’ housing in San Francisco, where she experienced this firsthand. The team was working with the developer organization, Swords to Plowshares, to explore how the FitWel certification framework could help them design for health for the future residents.

In the Fitwel program “no smoking” regulations are considered very important for community health. After all, everyone knows that smoking is bad for you, and for the people around you. But when learning about the mental health issues veterans were experiencing, Anne heard a different perspective:

ANNE TORNEY: Our clients said, you know, when I’m walking around the building and there might, somebody might have triggered somebody else and there’s an altercation about to happen. He said, “I used to smoke. I don’t smoke anymore. But I have a pack of cigarettes that I carry with me. And sometimes I can come upon one of these situations and offer folks a cigarette.” And he said, “there’s nothing better to just, like, calm things down. That’s a way more expansive view of mental and physical health than the typical universe of health thinking wants to embrace, but was really specific to those particular residents. So we couldn’t get that point in FitWel, even though it ultimately served the residents.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: Listening to this story reminded me again that integrated design is not about maxing out the points in a rating system but is about designing for the needs and priorities of the people who will live there. And after all, that’s what it’s really about.

[Short music]

KIMBERLY VERMEER: When these three strategies—early planning, a new approach to design development, and the inclusion of resident voices– are put into practice, magic can happen.

Krista had a great story about how integrated design transformed an affordable housing project she was involved in, a new construction project geared towards working artists in North Minneapolis.

KRISTA EGGERS: One of their goals in this project was to reflect the culture of the folks living in the building. So, to have local art, you know, sculptures or murals, et cetera, outside of the building, to really reflect the working artist who were going to be living here. They also had another goal of encouraging more physical activityamongst their residents. And although those were two goals that they were holding at the outset, they did not think that they were compatible, and they thought they were going to have to drop one or the other to meet their budget constraints.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: When there are multiple resident priorities, it can be challenging to see them as aligning with the “North Star” mission that Krista described earlier. But Krista saw that having resident priorities clearly identified at the outset of a project can actually encourage that alignment.

KRISTA EGGERS: Going through an integrative design process, they actually came to a wonderful conclusion and end result where they ended up developing several different sculptures created by local artists in Minneapolis that also were designed to encourage physical activity. So these beautiful sculptures that were also bike racks, for instance. These beautiful sculptures which were playground equipment for kids. And so, with a little thought and effort and coming together through this integrative design process, they were able to really accomplish both objectives which they wouldn’t have been able to do if they were considering them separately.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: Through the integrated design process, the project team was able to take a step back and work creatively to meet all project goals, even the ones that seemed to be at odds at a first glance.

The solution of interactive public art is more than a sum of its parts: integrating art and exercise together amplifies the benefits of both, actively engaging the residents and community.

This story demonstrates the power of integrated design to deliver comfortable, healthy, green projects. But more than that, it shows that, implemented the right way, integrated design is about justice: for families, neighborhoods and communities. Walker reflects on this larger view:

WALKER WELLS: I do see opportunity for integrated design, which is really looking beyond the building. The green affordable housing is a microcosm of urban sustainability and we would have these little jewel boxes of green, affordable housing throughout our city. But it was unclear to the degree to which they were really transforming the neighborhoods around them. The discussion about resilience is shifting that. And we’re starting to talk about, “Well, in what way could this building function as a resilience hub for the broader community and not just be a safe place for the residents, but a place of refuge for other people in the community?” So then it becomes not sort of an isolated jewel box, but sort of a catalyst for change in the broader neighborhood.

KIMBERLY VERMEER: Through integrated design, projects act as instigators at a larger scale, for an ecosystem of green communities. In this way, integrated design empowers practitioners to see their green building practice as a part of a larger system of cultural meaning.

[Outro music]

KIMBERLY VERMEER: Thanks to everyone who shared their passion and expertise: Walker Wells, Anne Torney, Tara Baruaskas, Krista Eggers, and Ray Demers.

If you want to read more about Integrated Design, check out the book that Walker Wells and I wrote, Blueprint for Greening Affordable Housing. The book is available from the publisher Island Press, as well as Amazon and Barnes & Noble. You can also search for “Blueprint for Greening Affordable Housing” at www.Bookshop.org, to support an independent bookstore near you.

If you want to learn more about the 2020 Enterprise Green Communities Criteria, you should check out our mini-sode with Krista and Ray, where we discuss how these guidelines can help teams build better projects.

This was the Green in Action podcast, where we explore green leadership in affordable housing.

Thanks for listening! You can find us on Twitter at @UHIPodcast. Subscribe to us wherever you listen to podcasts, and rate us and review us on Apple Podcasts. Thanks for doing that – it helps spread the word about Green in Action This episode was produced by Kimberly Vermeer, and Klara Kaufman. Sound engineering and audio editing by Carl-Isaak Krulewitch. Music by Matt Vermeer. Kimberly Vermeer is the Executive Producer. Green in Actionis an Urban Habitat Initiatives production.